In prison, inmates are stripped of individual identity. They are given identical clothing and must wear a specific number to replace their name. Self-expression must be enabled even for the most disenfranchised members of society. When art is supported in prisons it allows inmates to have a personal identity while allowing a more positive and constructive environment to exist.

Individuals serving sentences can explore self-expression and translate complex emotions into physical objects by creating art. Although prisoners are limited as to what supplies they may use, just one look at some of the art being produced one can see the emotion that must have gone into their artwork. An article for the New York Times supported art as a form of therapy in prisons. “Art-making is one way inmates can combat the “mortification process,’ the loss of self suffered by prisoners. It is a way to remain fully alive in a place that deadens the spirit.” Art allows prisoners to put energy towards creating something positive, something that others get to experience and even may get joy from.

Furthermore, when inmates are able to produce something of their own a sense of pride may be found. Generally, people who have made bad decisions may be a victim of their circumstances. They may have never learned right from wrong or had to violate laws for survival. Complex emotions may be better understood by prisoners when they can make something of their own and have a better sense of individuality. “‘I don’t have much of a legacy,’ Jeffrey Sutton, who is serving 41 years for armed robbery, said of his life. ‘This is something positive that helps me focus on getting out,’ he added, daubing flecks of green onto the leaves of a jungle vine,” (Brown). Art allows prisoners to transmit messages and convey their emotions.

Currently in California, the role of both visual and performing arts in prison is increasing. Established artists such as Guillermo Aranda can serve as mentors for prisoners by visiting and teaching at prisons. “The mural class for high-level offenders is part of a new initiative by the State of California to bring the arts — including Native American beadwork, improvisational theater, graphic novels and songwriting — to all 35 of its adult prisons, from the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility near the Mexican border to Pelican Bay, the infamous supermax just shy of the Oregon line,” (Brown). Furthermore, “In (California with) a political climate in which federal arts agencies are under siege, the state has allocated $6 million annually for the Arts in Corrections program, a figure set to rise to $8 million next year,” (Brown). California serves as an example of letting the arts expand in prisons, and the great outcome of it is evident in the art produced.

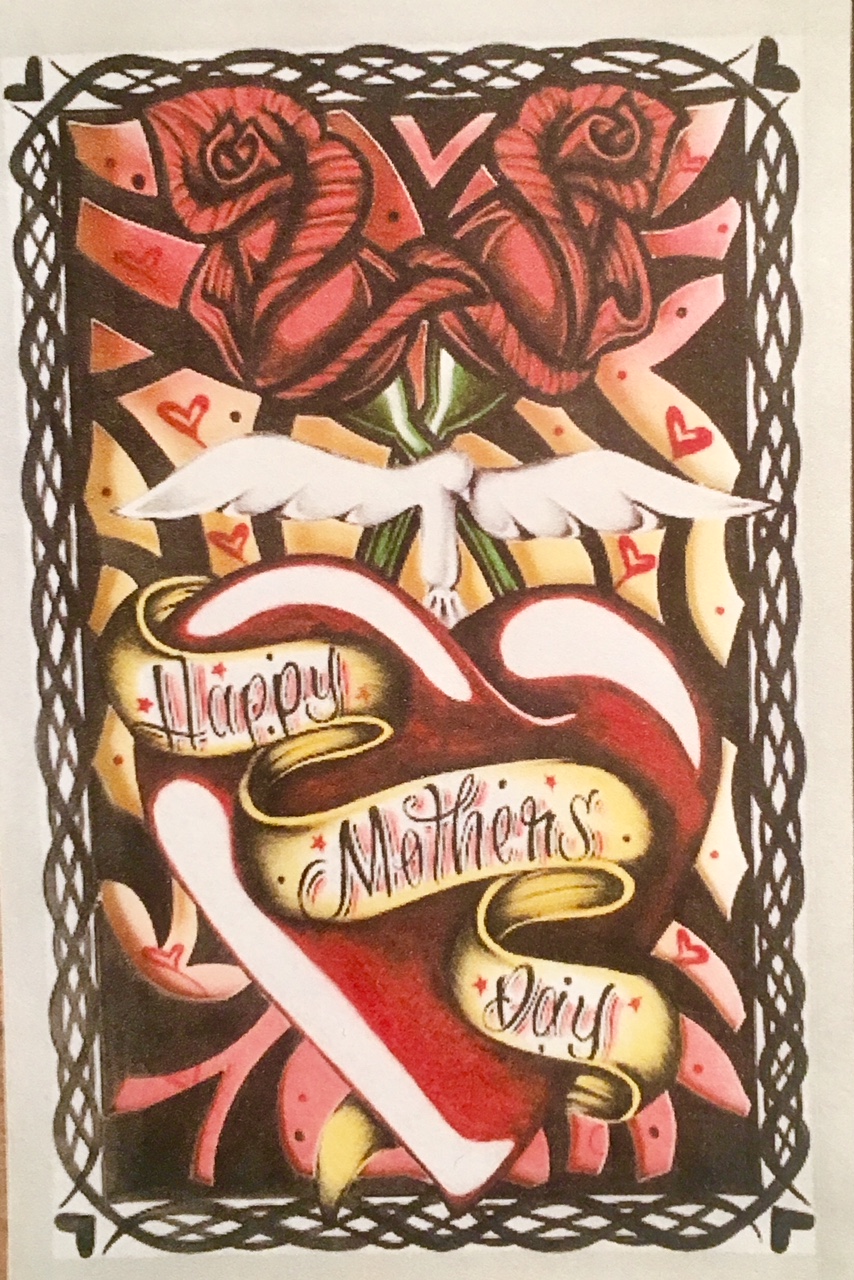

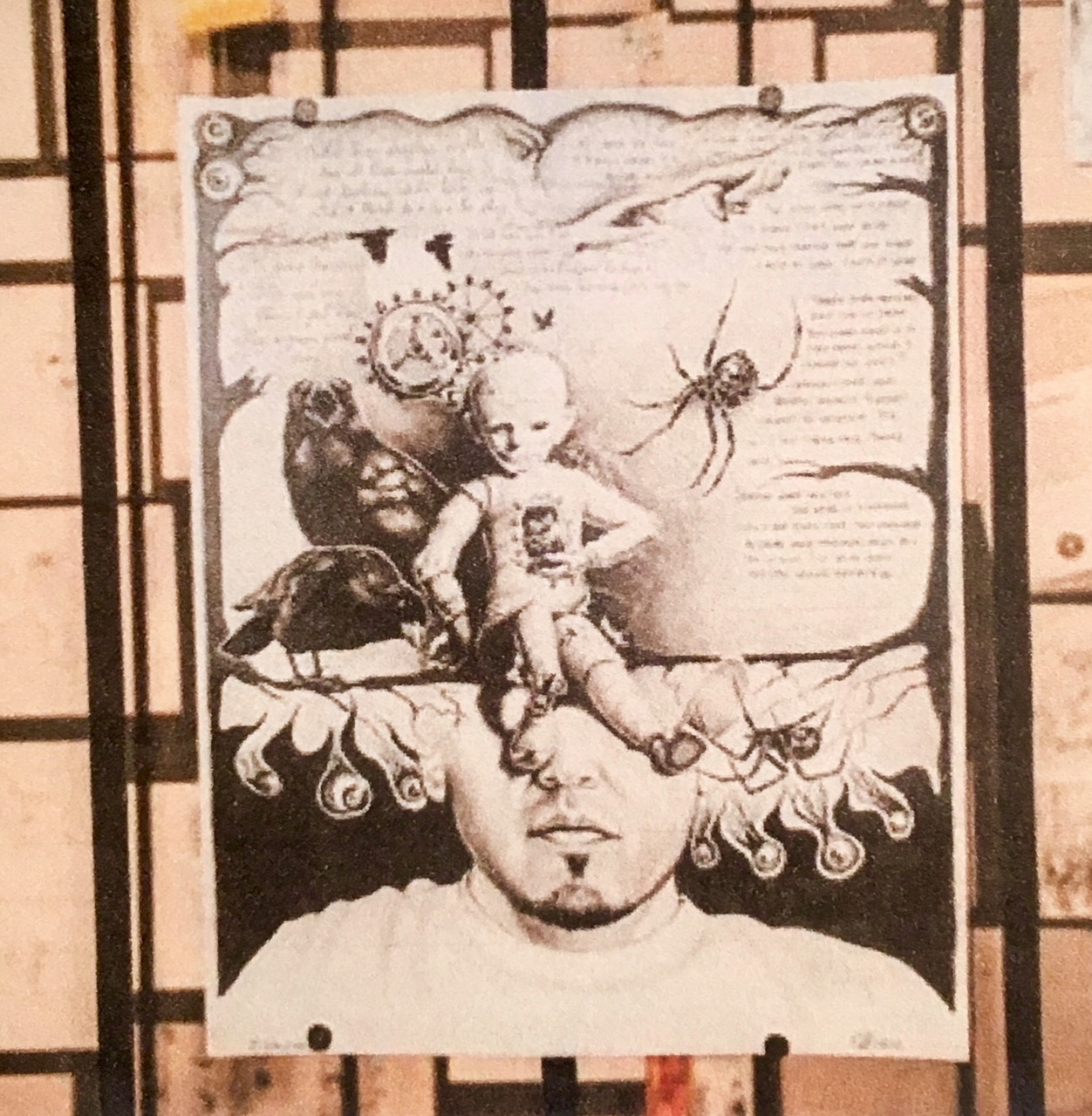

Art has proven to be very therapeutic, from calming paint strokes to releasing scribbles. Psychology Today believes that art allows for a greater understanding of emotions and that it “can be used as a springboard for reawakening memories and telling stories that may reveal messages and beliefs from the unconscious mind,” (Psychology Today). I was inspired to write this when I saw the art my good friend’s mother, Jamie Weinstein, received from inmates at San Quentin. She is involved in several advocacy councils for prisoners and has several pen pals. The emotion was visible on the piece I saw hanging in Weinstein’s living room. Visual and performing arts overall allow for personal reflection and a greater personal identity to be formed from even the most disenfranchised members of society.

Works Cited

“Art Therapy” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers

Brown, Patricia Leigh. “No License Plates Here: Using Art to Transcend Prison Walls” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 Apr. 2017

“How A Prison Art Program Is Promoting Self-Reflection In Incarcerated Men” Google Search, Google

“Making Art in Prison” The New York Times, The New York Times, 4 Apr. 2017

Interview with Jamie Weinstein. Conducted over in person in 2017 and email June 2018. Art images courtesy of Jamie Weinstein.